A recurrent feature of scandal is that they rarely break all at once; rather, scandals tend to metastasize as conspiracies enlarge, trust evaporates and more information comes out. President Park Geun-hye’s current troubles do not appear anywhere near done, as the lines of both influence and corruption related to her confidante and advisor Choi Soon-sil continue to surface.

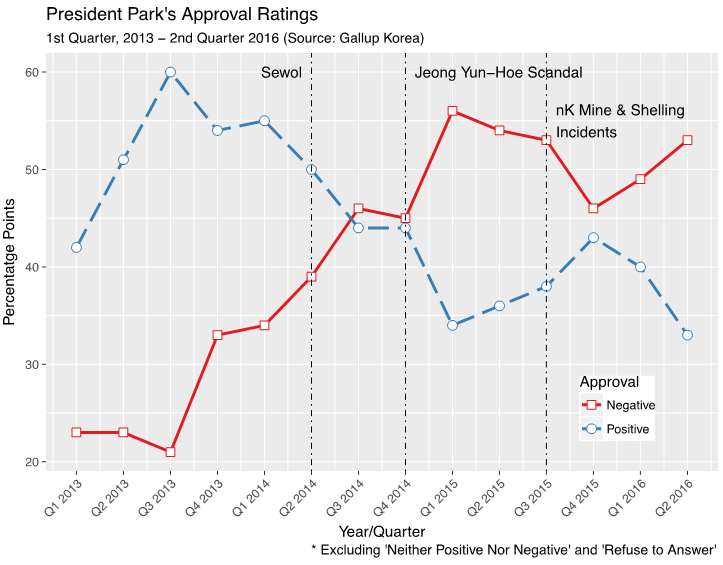

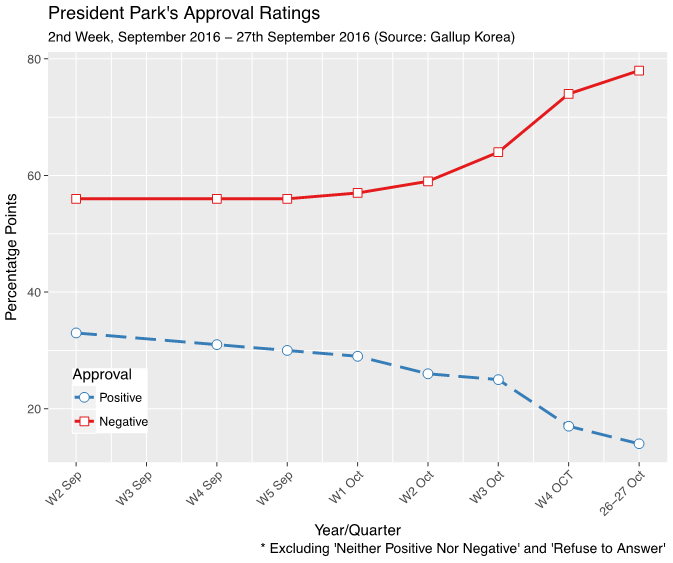

But one thing is clear: the public is proving relentlessly unforgiving. The president’s approval ratings had already suffered the near-secular decline typical of Korean presidents, pushed along most notably by the Sewol ferry incident and the scandal surrounding Jeong Yun-hoe, also embroiled in court politics. (See past posts on scandals here, here, and here.) Since the scandal broke, however, her numbers have gone into a virtual free fall and she is facing mounting demonstrations as well. We start today with the polls and an overall timeline, turning tomorrow in more detail to the substantive charges and the constitutional and political issues surrounding Park’s presidency.

The basic timeline of the scandal has been covered reasonably well in the American press; as usual Choe Sang-hun at the New York Times provides good reporting and we link to a number of general Korean sources below. But as with all scandals, the detail is important and the scope of the President’s problems are unusually large; without seeing that full scope it is hard to understand why she is facing such difficulty.

First, the scandal has deep roots. Its lurid overtones stem not simply from the influence exercised by Choi Soon-sil—compared to Svengali or Rasputin—but by Park Geun-hye’s long-standing relationship with her father Choi Tae-min. A quasi-religious and cultish figure, Mr. Choi had befriended Park Geun-hye after the assassination of her mother in 1974 and appeared to act as a controlling guide. According to a 2007 cable from U.S. Ambassador Alexander Vershbow released by Wikileaks in 2011, Mr. Choi had “complete control over Park’s body and soul during her formative years and that his children accumulated enormous wealth as a result,” claims Park denied (a feature in Joongang provides the outlines).

Starting in July, the Chosun Ilbo began producing exclusive reports on what appeared to be going on in the Blue House. On July 18, the Chosun first wrote about corruption allegations surrounding Presidential Chief Secretary Woo Byung-woo. The Minjoo Party also raised allegations during the National Assembly Audits that Ms. Choi influenced the appointment of Woo in the first place. On July 27, Chosun Ilbo first reported on the allegations about MIR Foundation, followed on August 2 by the first reports on K-Sport Foundation. MIR and K-Sports allegedly collected 48 and 38 billion won to promote and support Korean culture and sports from leading chaebol, but had done so with surprising alacrity and with evidence that funds might have been diverted to entities controlled by Choi.

As we have argued elsewhere with Jong-sung You, freedom of expression in South Korea has taken a hit in recent years. Among the many disturbing features of the current scandal are efforts at intimidation, and of a newspaper that is hardly associated with the left. On August 22, the Blue House called the Chosun an example of “corrupt vested interests.” A week later, Assembly Member Kim Jin-tae held a press conference raising corruption allegations against Chosun’s editor. The editor resigned the next day and reporting on the issue miraculously stopped.

In the third week of September (22th, 24th, 26th), however, the drip of news finally forced the Federation of Korean Industries, an organization representing the interests of the country’s largest firms, to deny any wrongdoing associated with the funding of the two foundations. Yet it was still another month (October 20) before the president was constrained to mention the issues raised by the National Assembly Audits, claiming that all contributions were voluntary and “anyone who committed illegal activities in relation to these foundations, including fund management, will be severely punished.” Statements such as these are always dangerous in a scandal: they promise justice but can lap at the door of the president herself.

Another stream of the story that had particular resonance in Korean public consciousness concerned charges that Choi had used her influence to get her daughter Yoora Chung admitted to Ewha University. If you want to poke a hornet’s nest in Korea, just hint at corruption regarding access to education. Over the next month, a steady stream of information dripped out about a host of ways—large and small—that Choi had influenced Ewha on her daughter’s behalf. The pressure finally led to the resignation of Ewha’s chancellor on October 19, only two days after a faculty meeting saying it would never happen. The Ewha scandal also generated student protests that have now become a non-trivial background feature of the drama.

In short, a variety of lines of attack had already opened prior to last week, and we return to them in more detail in a subsequent post. Ironically, the very same day the scandal took a more decisive turn on Monday October 24th, the President had sought to deflect attention from Choi’s influence by proposing that South Korea’s recurrent lame duck problem be solved by reversing the country’s no-reelection rule, although to go in effect after Park’s term ended. That very evening, a CNN affiliate, JTBC, claimed it had come into possession of an abandoned computer of Choi's demonstrating that she had been granted access to classified material.

It was these revelations that led to President Park’s abject public apology on Tuesday (official Blue House video here). While there is no official translation, Park defended herself by reference to her intent: "I had pure intentions to more carefully attend to the matters but regardless, I am sorry for causing the public to be concerned, surprised and hurt. I deeply apologize to the people." By the weekend, Choi had issued an apology through her lawyer and Park had fired her chief of staff and no fewer than seven additional aides who were identified with Choi’s unusual access to the president. Choi was in talks with prosecutors and prosecutors were even seeking access to the Blue House itself to search for possible evidence of criminal wrongdoing on the part of her advisors. Multiple lines of criminal investigation had been opened, from the foundations to release of classified materials.

On Monday: a more detailed view of possible lawbreaking and the constitutional and political implications.

General Korean Sources

- http://www.yonhapnewstv.co.kr/MYH20161030002700038/

- http://news.mt.co.kr/mtview.php?no=2016102619598262957

- http://www.ytn.co.kr/_ln/0102_201610301314002612

- http://news.sbs.co.kr/news/endPage.do?news_id=N1003858102

- http://news.khan.co.kr/kh_news/khan_art_view.html?artid=201610281538001&code=940202

- http://www.yonhapnews.co.kr/politics/2016/09/29/0501000000AKR20160929058352004.HTML

- http://www.yonhapnews.co.kr/bulletin/2016/10/25/0200000000AKR20161025080051004.HTML

- http://www.asiae.co.kr/news/view.htm?idxno=2016102811015858751