The labor market improvement accelerated in March 2021 as employers added 916,000 jobs, a very rapid pace but one that will need to be sustained in order to repair the economy. Overall the economy was 10 million jobs below its pre-pandemic trend, and if the March pace of jobs gains is sustained, it will take another 14 months to close the jobs gap.

At the same time the official unemployment rate fell to 6.0 percent while the participation rate edged up by 0.1 percentage point. The unemployment rate has been falling steadily, even while the labor force participation has remained at a relatively stable, but low, level since last summer.

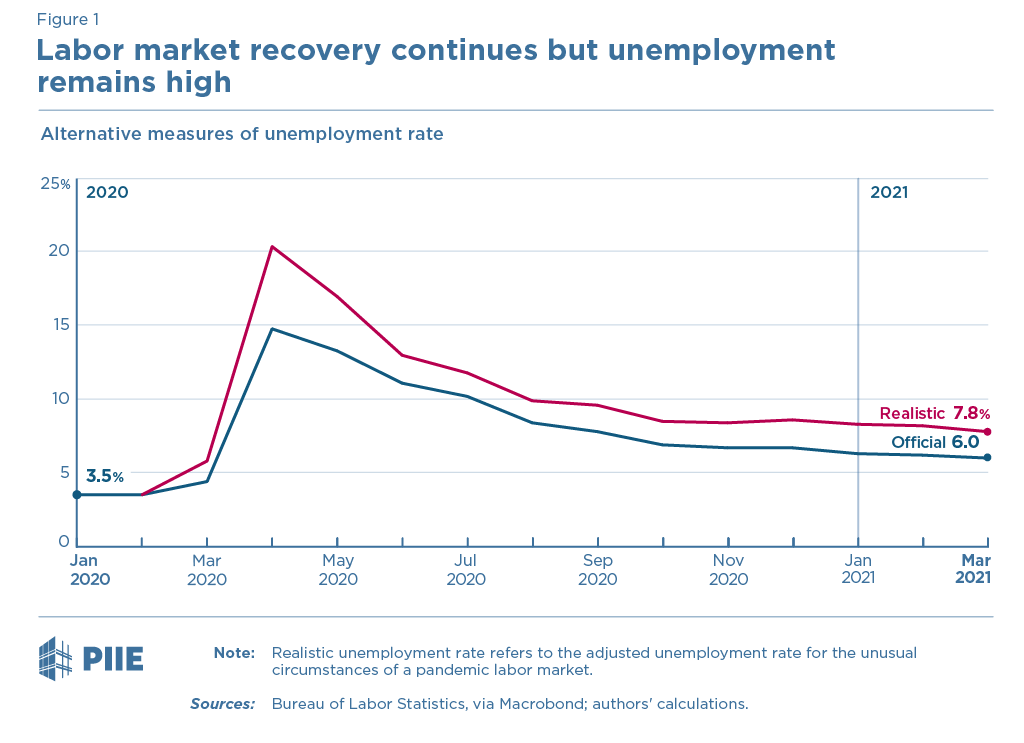

Our estimate of the realistic unemployment rate, which adjusts for a misclassification error and the unusually large withdrawal of millions of people from the workforce, fell to 7.8 percent (as compared with a high of 10.0 percent in the financial crisis). Another concept, the fixed participation rate unemployment rate, cited by Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, was 9.1 percent; the comparable concept peaked at 11.8 percent in the financial crisis.

The realistic unemployment rate fell slightly in March but remains elevated

The headline unemployment rate was 6.0 percent in March, down slightly from 6.2 percent in February. This concept works well in normal times but has had some deficiencies in the context of the pandemic. In response to these unique circumstances, we have been publishing monthly updates since June 2020 tracking what we call the "realistic unemployment rate" as shown in figure 1.

The realistic unemployment rate adds 637,000 workers who reported being "not at work for other reasons" as unemployed and also adds 2.4 million workers to the labor force to reflect the fact that the decline in labor force participation has been unusually large, even conditional on the overall economic weakness and adjusted for changing demographics (note that this is only a portion of the 3.9 million workers who have left the labor force since February 2020). This measure was 7.8 percent in March and is intended to be historically comparable to the official unemployment rate. The realistic unemployment rate fell faster than the official unemployment rate in March as the labor force participation rate ticked up, and the improvement has been faster than in recent months.

Recently many, including Yellen and Powell, have cited what we call a "fixed participation rate unemployment rate." This measure fell from 9.5 percent in February to 9.1 percent in March. This concept is more straightforward than the "realistic unemployment rate" in that it simply assumes that all of the workers who have left the labor force since February 2020 should be treated as unemployed. An advantage of this approach is that it measures how much further the economy has to go until employment is back to where it was prior to the crisis. It has the disadvantage of not being comparable to official unemployment rates during previous recessions because, by construction, it is higher than the official unemployment rate. In the last recession the "fixed participation rate unemployment rate" peaked at 11.8. (Another downside of the "fixed participation rate unemployment rate" is that it does not adjust for demographic changes, as an aging population would be expected to reduce labor force participation, though this is a relatively small issue over shorter periods like a year.)

Since last summer we have also been tracking another concept, the "full recall unemployment rate," that adjusts for workers on temporary layoff as well as the unusually large decline in participation. This measure is increasingly less relevant as the number of workers on temporary layoff has fallen, but we include it below for completeness. The full details on the calculation of the realistic unemployment rate and the fixed participation unemployment rate are available here .

| Alternative measures of unemployment | |||||

| February 2020 |

January 2021 |

February 2021 |

March 2021 |

Change: Feb. 2020 to Mar. 2021 (p.p.) |

|

| Official | |||||

| Unemployment rate | 3.5 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 6.0 | 2.6 |

| Labor force participation rate | 63.3 | 61.4 | 61.4 | 61.5 | -1.8 |

| Realistic | |||||

| Unemployment rate | 3.5 | 8.3 | 8.2 | 7.8 | 4.3 |

| Labor force participation rate | 63.3 | 62.4 | 62.4 | 62.4 | -0.9 |

| Fixed participation rate | |||||

| Unemployment rate | 3.5 | 9.7 | 9.5 | 9.1 | 5.7 |

| Labor force participation rate | 63.3 | 63.3 | 63.3 | 63.3 | 0.0 |

| Full recall | |||||

| Unemployment rate | 3.5 | 6.9 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 3.4 |

| Labor force participation rate | 63.3 | 62.6 | 62.5 | 62.6 | -0.8 |

| Note: p.p. denotes percentage points. Change based on unrounded numbers. Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Macrobond; authors' calculations. |

|||||

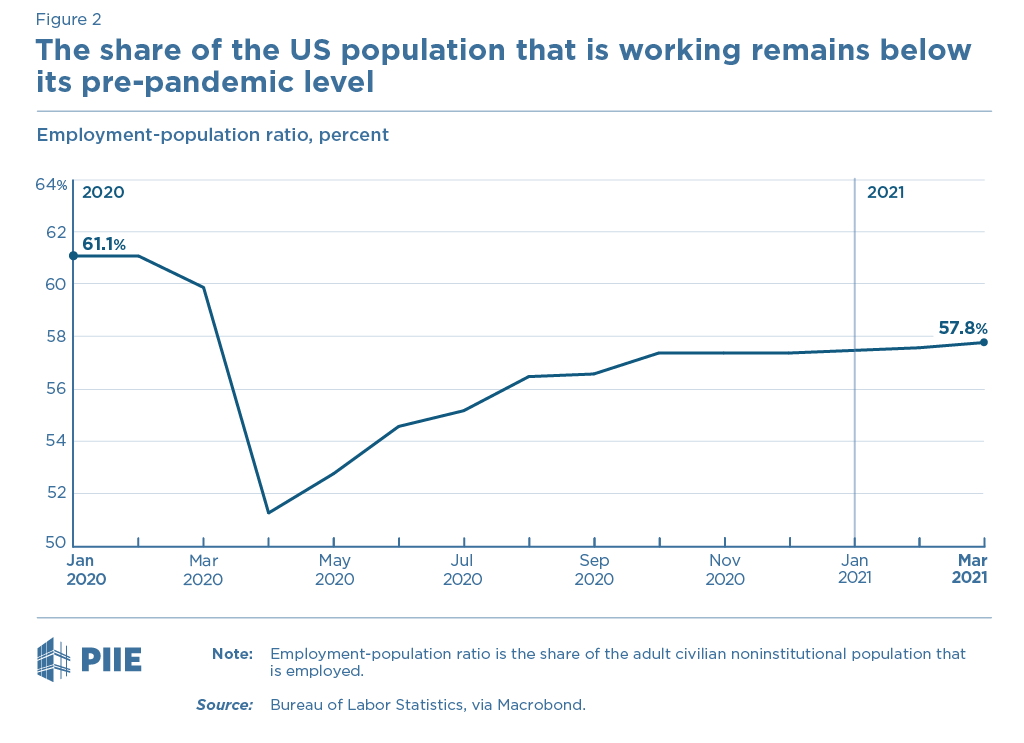

As the unemployment rate remains elevated, the employment-population ratio is 3.3 percentage points below its pre-pandemic value

Last month, the employment-population ratio, the share of the civilian adult population that is working, increased slightly. Overall, the employment-population ratio has fallen from 61.1 percent in February 2020 to 57.8 percent last month. The change in the employment-population ratio accounts for both the change in unemployment and the change in labor force participation and thus fully captures the change in employment. Our alternative measures of unemployment capture the abnormally large increase in the number of people who have stopped looking for work, but, like the fixed participation rate unemployment rate, the employment-population ratio accounts for the entire increase in labor force nonparticipation.

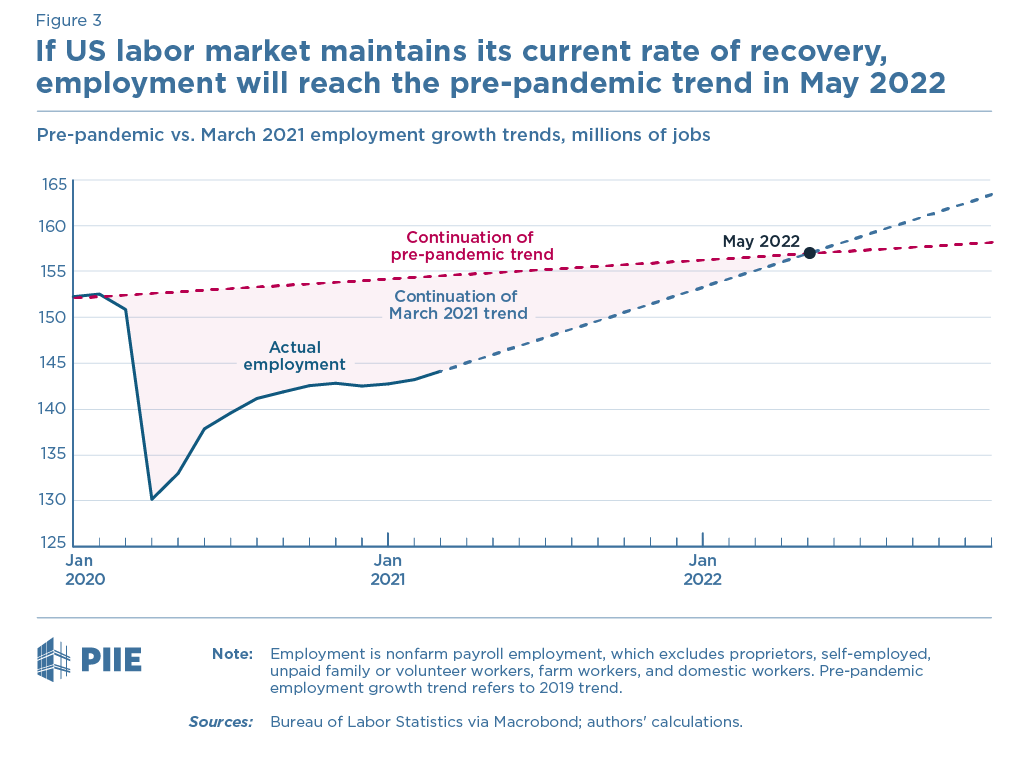

Overall employment is 10 million jobs, or 7 percent, below its pre-crisis trend—and at the March pace it will take 14 months to close the gap

A total of 8 million jobs have been lost in the thirteen months since the economy's peak in February 2020. If the 2019 pace of job growth had continued, the economy would have added about 2 million jobs over this period. As a result, total employment was 10 million, or 7 percent, short of where it was expected to be in March.

The shortfall in employment is larger than the shortfall in GDP. For the first quarter as a whole, employment was 7 percent short of trend. At the same time, based on the latest IHS Markit tracking estimates, GDP was about 4.0 percent short of trend in the first quarter. This disconnect appears to largely reflect the fact that workers with lower productivity have lost their jobs, reducing employment more than GDP. Over the coming year this process is likely to reverse.

The pace of job growth in March was extraordinary by normal standards but still would not be sufficient to return the US labor market to normalcy for 14 months, until May 2022 as shown in figure 3.

Conclusion

Understanding the data can help inform projections of the trajectory of labor market recovery. We saw an initial "partial bounce back" in the labor market in the late spring and summer of 2020, as the unemployment rate fell quickly at first as businesses reopened. Now we are in the midst of what appears to be another further bounce back as many economic activities are returning to pre-pandemic norms.

The prospects of the labor market over the next year will depend on the trajectory of the virus and how many people without jobs can quickly connect with their old jobs instead of undertaking the time-consuming process of finding a new job or even a job in a new industry. Virus cases have started to rise again even while deaths have generally fallen or levelled off—although widespread vaccination raises the prospect of normalization absent significant mutations. At the same time, the pace of job growth will need to pick up even further if the economy is to meet the widespread forecasts of something like a return to its full potential by the end of this year.

Data Disclosure

The data underlying this analysis are available here.

Related Documents

- Filefurman-powell2021-04-02.zip (1.26 MB)