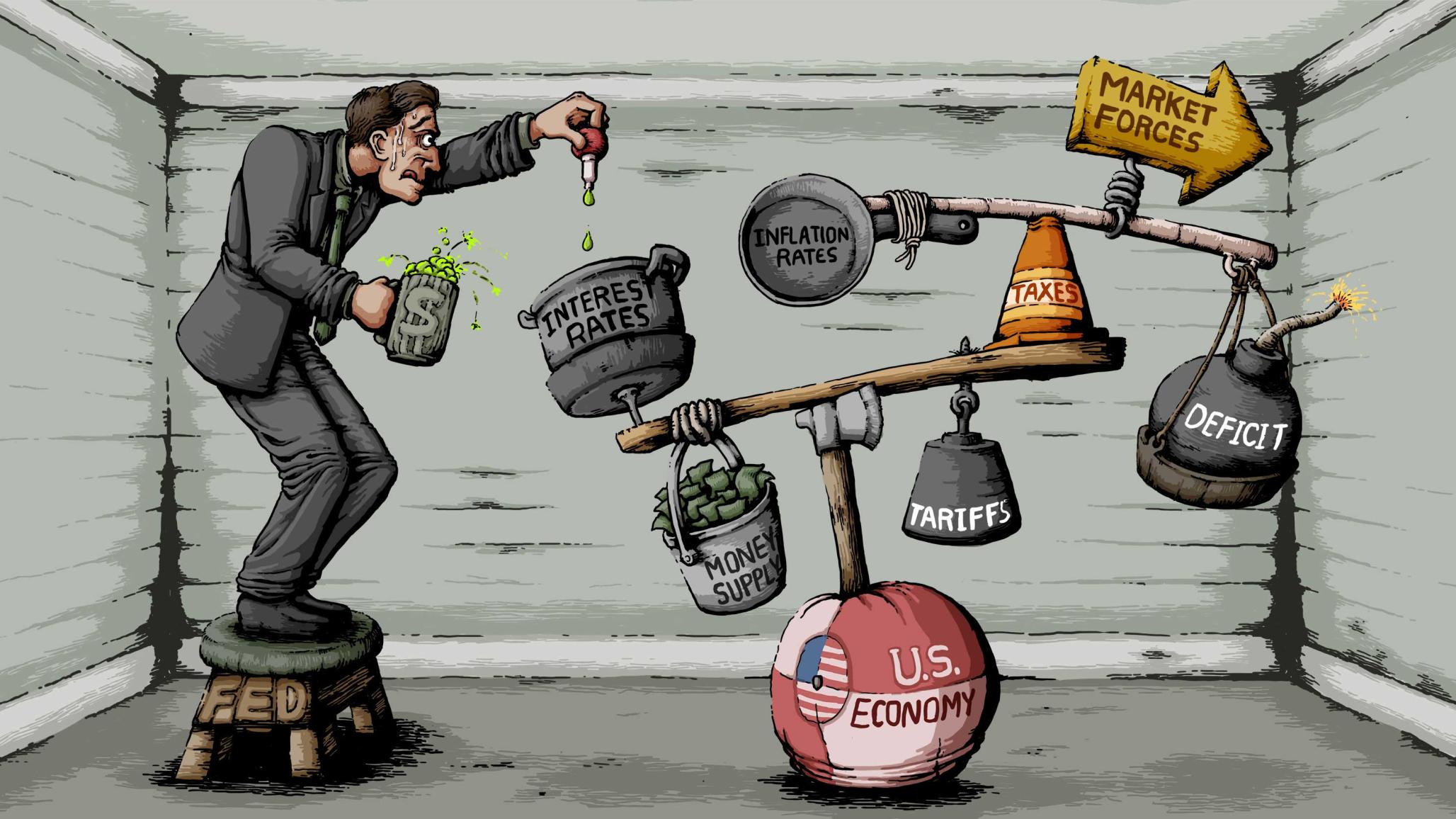

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC, or Fed) surprised no one at its September meeting by raising the target for the federal funds rate a quarter of a percentage point to a range of 2.00 to 2.25 percent. The FOMC has been tightening monetary conditions very slowly since late 2015. Its dilemma is a classic one for central banks—seeking to keep inflation at its target of 2 percent without causing an abrupt slowdown in growth. The FOMC also released new projections for key economic variables. The tension in the projections between a strong economy, with unemployment below its long-run level, and inflation stable at target remains as great as it was in June. In coming months, it is likely that inflation and inflation projections will rise or else the projection of the long-run rate of unemployment will fall.

The only notable change in the FOMC’s policy statement was the dropping of a sentence that characterized Fed policy as “accommodative.” In the press conference after the meeting, Chair Jerome Powell said that the funds rate is approaching a range in which policy may be considered neutral instead of accommodative. He also said that the purpose of the original language was to communicate the Fed’s intention to support a fragile recovery during the early months of tightening. Given the continued strong economic performance, the FOMC felt it was no longer appropriate to signal that the economy needs monetary support.

The FOMC raised its projection of GDP growth in the near term but otherwise made little change to its projections besides extending them to 2021. The projections show the unemployment rate roughly a percentage point below its long-run level through late 2021, yet inflation remains firmly fixed at 2.1 percent. These projections seem to defy the standard Phillips curve model of inflation that says inflation should increase as long as unemployment is below its long-run, or natural, rate.

When asked about this tension, Chair Powell stated that the effect of low unemployment on inflation is likely to be very small because inflation expectations are anchored so strongly. He said that it might take a very long time to return to the natural rate of unemployment. In June, Powell had stressed the possibility that the natural rate of unemployment might be lower than 4.5 percent. Although he raised this possibility again, it was not his primary focus. Neither the median projection nor the central tendency range for the long-run rate of unemployment changed from the June projections.

It strains credulity that a 1 percentage point gap between the unemployment rate and its natural rate would be expected to have essentially no effect on inflation over more than three years. As mentioned in this blog in June, the most likely resolution is that inflation, and projections of inflation, will rise above 2.1 percent in the next couple years. Some overshooting of the 2 percent target is not a bad outcome given the undershooting of the past few years. The Fed will have plenty of time to adjust its policy path, or reconsider its inflation objective, before any serious overshooting occurs.

In the press conference, a reporter asked Chair Powell about the FOMC's view on the supply-side impacts of the tax reform passed last December. Powell said he hopes it raises the economy's potential growth rate a lot, but the FOMC projections show no upward revisions in long-run growth. Last fall the White House argued that the tax reform would raise the economy's growth rate from 2 percent to "3 percent or more" over the next 10 years. Between September 2017 and September 2018, the median FOMC projection of long-run growth was unchanged at 1.8 percent and the range across all FOMC participants narrowed from 1.5 to 2.2 percent to 1.7 to 2.1 percent. Not a single FOMC participant, including Chair Powell, projects growth in 2021 and beyond above 2.1 percent.