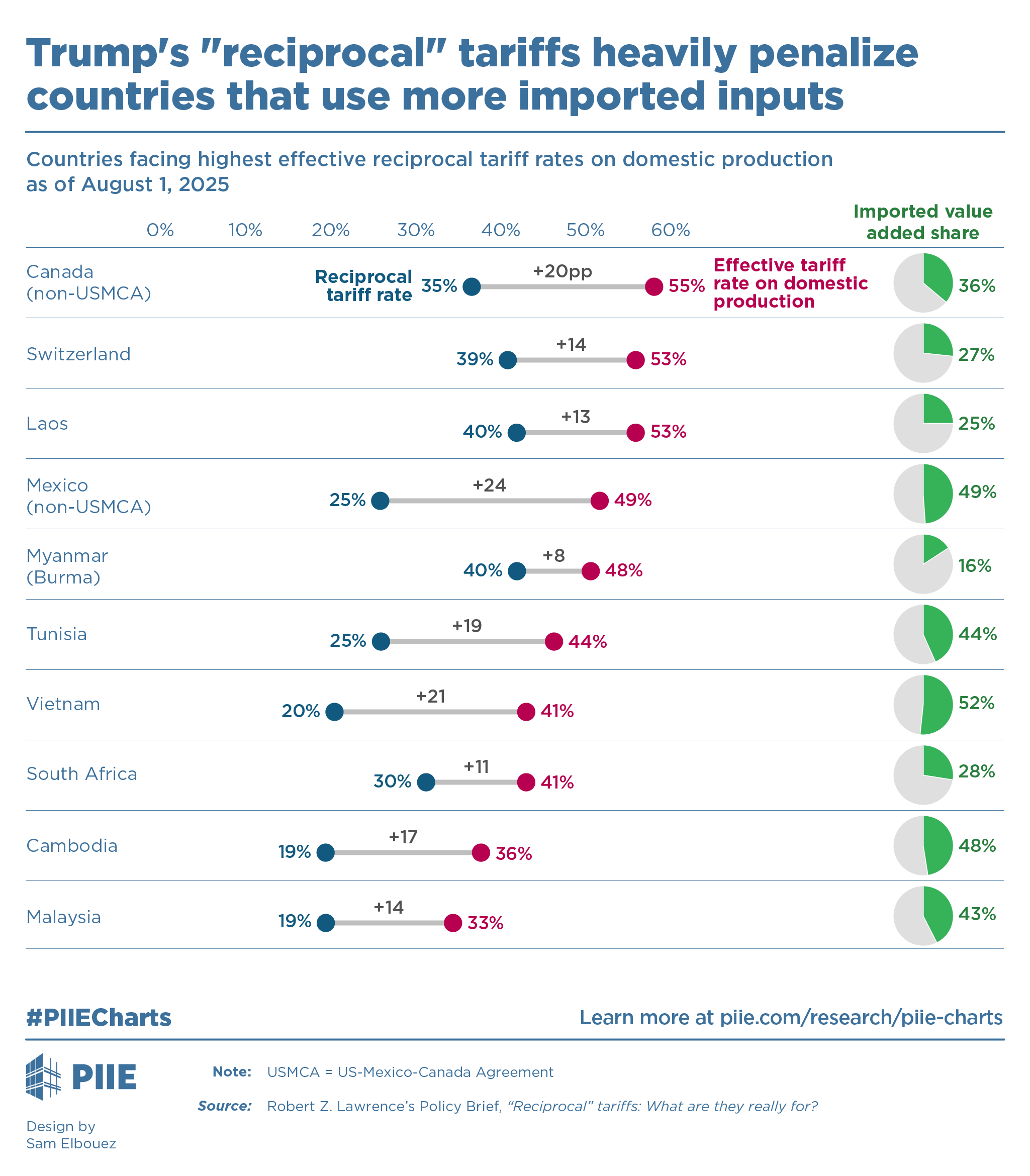

President Donald Trump’s so-called reciprocal tariffs went into effect August 1 at 15 percent or higher for many US trading partners. But the method used to calculate these rates ignores how global value chains work, greatly penalizing countries that use more intermediate inputs from other countries in their exported products.

US tariffs are assessed on the gross value of goods exported from the country where production or assembly occurred before shipping to America. But, if that country uses some inputs imported from other countries, the effective tariff on that country’s domestic production—call it the penalty rate—will be higher than the nominal tariff. This is because the tariff rate is applied to the total value of an exported product—both the imported and domestically produced components. A manufacturing firm may have to absorb that additional charge on those inputs to remain competitive.

As an example, 48 percent of the gross value of Vietnam’s manufactured exports are produced in Vietnam, with the remaining inputs coming from elsewhere. But the new US tariff rate of 20 percent will be applied to 100 percent of the value of Vietnam’s exports. That means Vietnam’s domestically produced components bear an effective tariff, or penalty rate, of 41 percent.

Also striking are the effective penalty rates threatened on goods that do not qualify for the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) from Canada (55 percent) and Mexico (49 percent).

Exporters that the world relied on after diversifying away from Chinese exports, like Mexico and economies in East Asia, will face these higher effective penalty rates to the extent that their exports include inputs from elsewhere.

In the process, the US tariffs will inflict considerable economic damage on many economies and will do little to reduce America’s overall trade deficits.

This PIIE Chart is adapted from Robert Z. Lawrence’s Policy Brief, "Reciprocal" tariffs: What are they really for?

Data Disclosure

This publication does not include a replication package.