The US labor market continued its recovery in March. Payroll employment rose by 431,000 in March. While the gain was a bit lower than most analysts had expected, the estimates of employment in both January and February were revised up, putting average monthly growth in the first quarter of 2022 at a robust 562,000, as shown in figure 1. The unemployment rate fell 0.2 percentage point in March to 3.6 percent and is now roughly back to its pre-pandemic level.

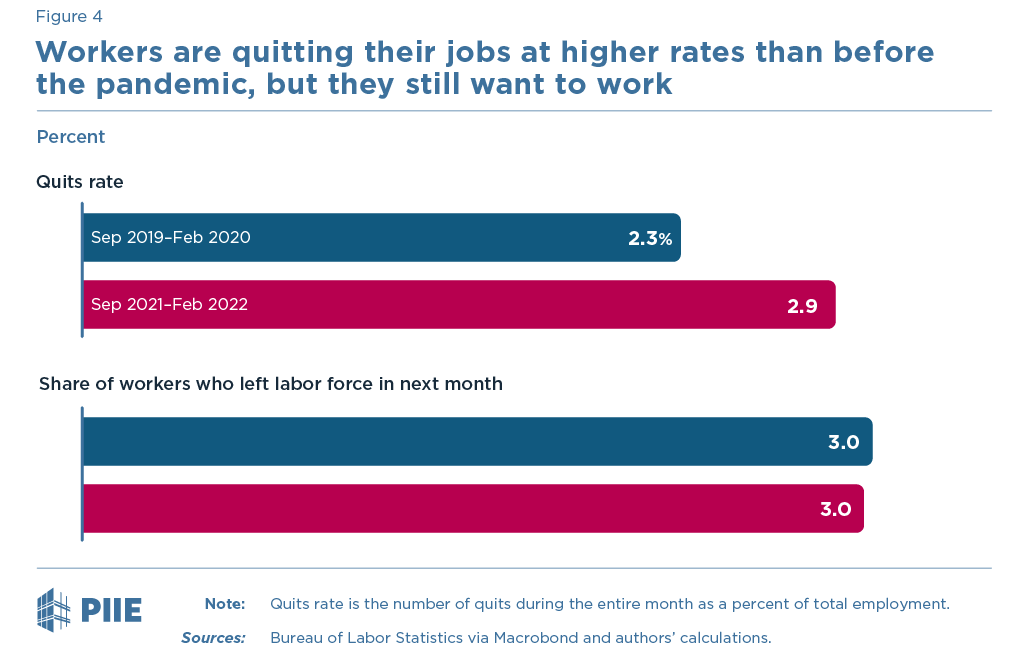

Notwithstanding the low unemployment rate, the level of US employment remains materially below the level of pre-pandemic forecasts. The gap reflects an ongoing slow recovery of labor force participation (which rose only 0.1 percentage point in March). The limited recovery appears to be driven less by the so-called "Great Resignation" than by the only-gradual return of workers who were laid off early in the pandemic.

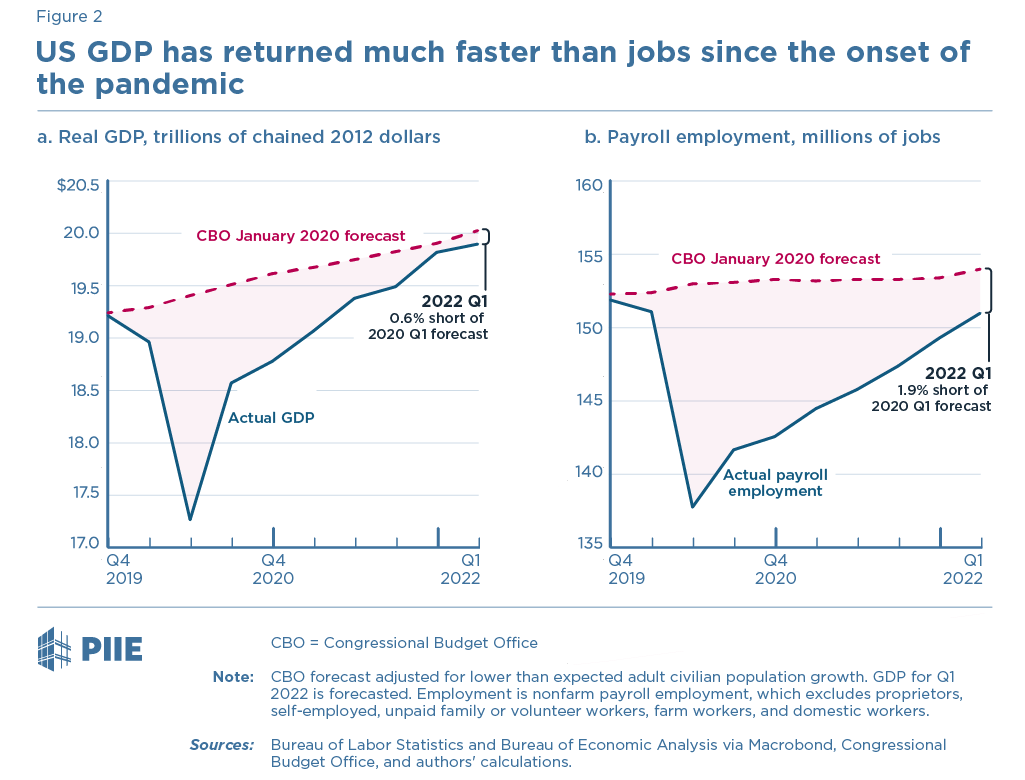

The shortfall in employment relative to pre-pandemic expectations stands in contrast to the performance of real GDP, which is nearly back to the level suggested by earlier forecasts. This contrast partly reflects higher productivity growth during the pandemic. With the full explanation for the higher productivity growth still unclear, it is difficult to say whether such growth will persist, but the gains to date are good news for the US economy. History suggests that higher productivity growth will translate into higher average wages over the longer run.

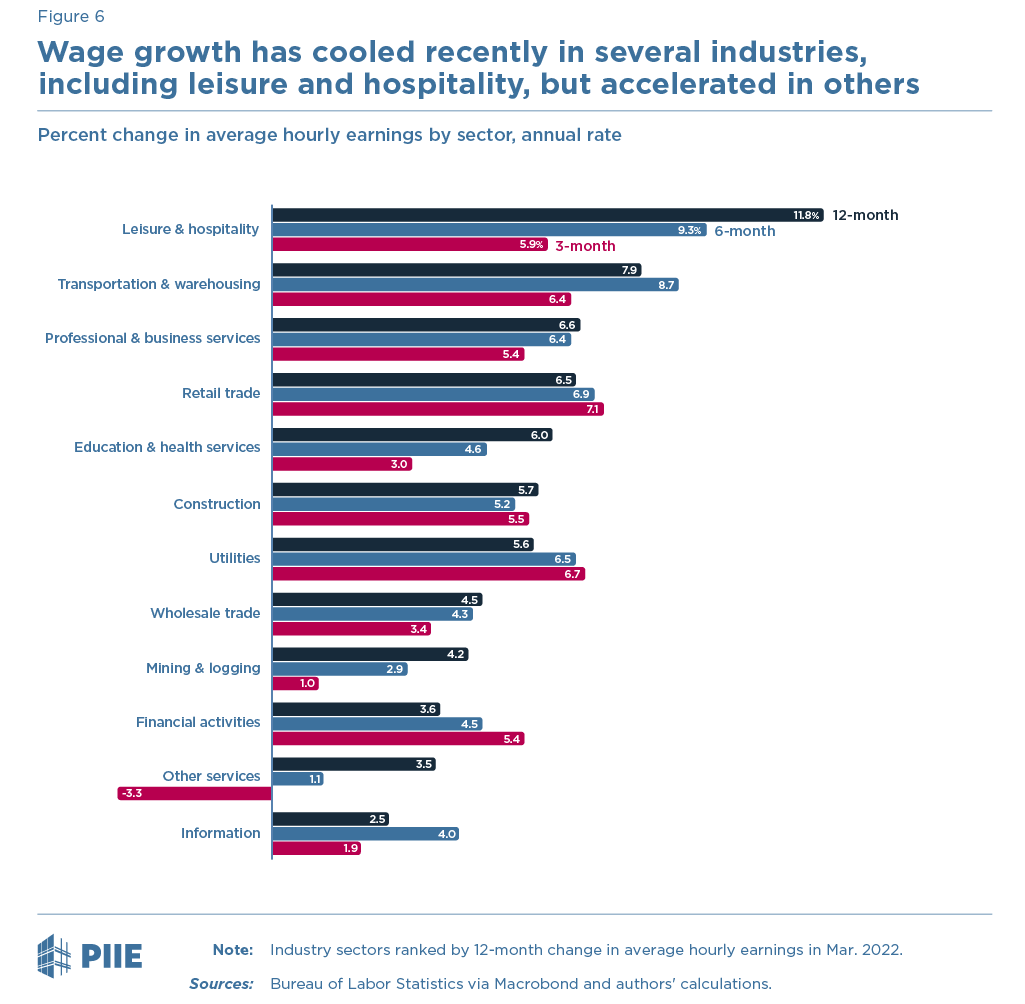

From a shorter-run perspective the productivity gains have likely held firms' unit labor costs lower than they would otherwise be. This is a welcome development given the upward pressure on wages imparted by worker shortages. Average hourly earnings were up 0.4 percent in March after a marked slowdown in their growth in February, and the 12-month change continues to run more than 2 percentage points higher than its average in the decade leading up to the pandemic. While wages appear to be moderating in some sectors, like leisure and hospitality, they have picked up in others.

All told, the March labor market report was positive on many dimensions. But it did little to assuage concerns that the Fed will need to sharply tighten monetary policy to curb price inflation, which comes with the risk of materially setting back or reversing some of the broader economic recovery.

Despite strong growth in payrolls in recent months, the employment recovery lags the recovery of real GDP

As seen in figure 2, real GDP and nonfarm payroll employment showed similar sharp declines just after the pandemic set in, but the recovery since then has been stronger for GDP than for employment. Real GDP is now nearly equal to the Congressional Budget Office's (CBO) earlier forecast (adjusted for slower-than-expected population growth), whereas nonfarm payroll employment (also adjusted for slower population growth) still falls short of the earlier forecast by nearly 2 percent.

The US economy is able to produce as much as expected with fewer workers partly because average weekly hours, at an average of 34.8 over the pandemic recovery period, have been running higher than their 2019 average of 34.4.

Another part of the explanation is that more output is being produced per hour of work. Labor productivity growth in the nonfarm business sector has averaged 2.3 percent since the end of 2019, compared with an average of 1.3 percent in the five years prior to the pandemic. The full explanation for the step-up in productivity growth is not clear, but it likely reflects a combination of several factors. Some factors—like firms' investments in labor-saving technologies, businesses generally emerging leaner from the pandemic, and, perhaps, a higher pace of innovation during the pandemic period—are likely to be lasting and may continue to contribute positively to productivity growth. But other factors—including a different composition of employment (with workers in lower-productivity industries most likely to have been laid off during the pandemic) and an unsustainable boost from businesses pushing their existing employees to keep up with high demand—may go into reverse and be a drag on productivity growth.

What are the implications of higher productivity growth? History suggests that, over the long run, workers who become more productive will see higher real wages than they otherwise would. In the short run, additional productivity growth may help restrain unit labor cost growth, which should relieve some pressure on firms to pass higher wages along to prices. (Wage growth, however, has been much faster than productivity growth, so unit labor costs have still grown much faster than before the pandemic.) The significance of these effects will depend on how long faster productivity growth persists.

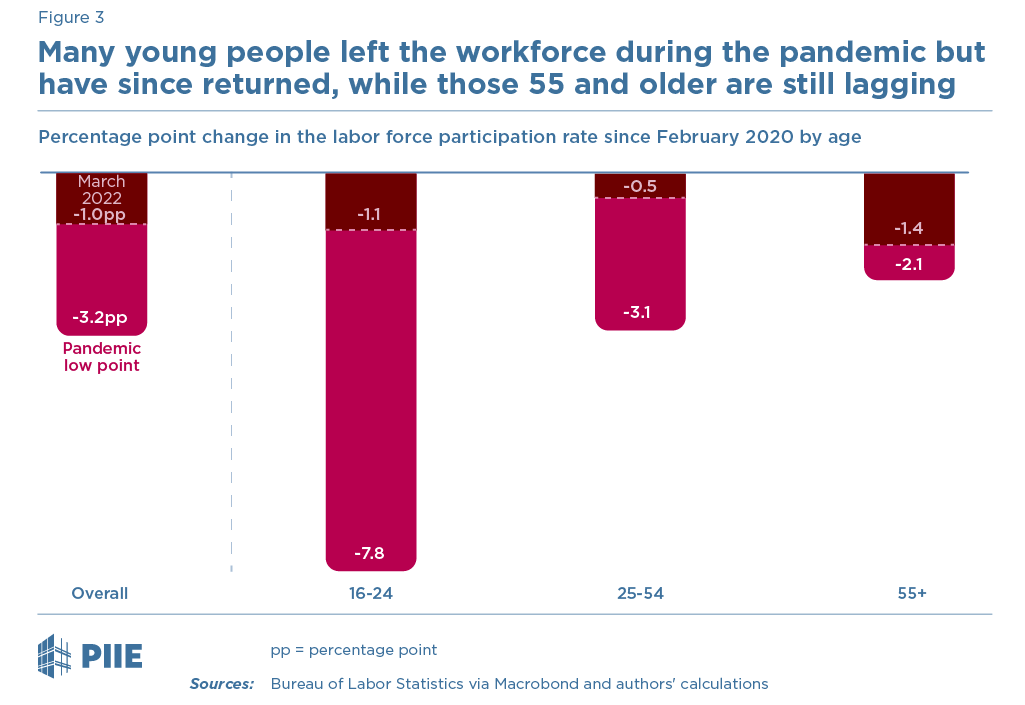

Labor force participation is rising, but how much it will rebound remains an open question

The labor force participation rate rose a total of 0.5 percentage point in the first three months of 2022, and it has now recovered roughly ⅔ of its initial drop in the early part of the pandemic. As can be seen in figure 3, the degree of recovery in labor force participation differs by age. The smallest recovery (relative to the initial drop) has been for individuals who are age 55 or older, and that group now has the largest remaining shortfall. One might expect departures from the labor force by older workers to be more lasting than that of younger workers given the likelihood that wealth gains during the pandemic accelerated retirements—although some evidence points to a step-up in "unretirements" in recent months.

Labor force participation has recovered more slowly than one might expect given the strength of labor demand since last summer. The quits rate has jumped to unusually high levels, but the "Great Resignation" does not appear to be the primary reason that labor force participation is depressed. As can be seen in figure 4, since last fall, the share of workers who stopped working and dropped out of the labor force is about the same as in the comparable period prior to the pandemic, consistent with an abundance of commentary suggesting that most workers are quitting their jobs to take better ones. The gradual recovery of labor force participation is thus more likely a reflection of some people who were laid off during the early part of the pandemic facing frictions in returning to the labor force or choosing to delay their return.

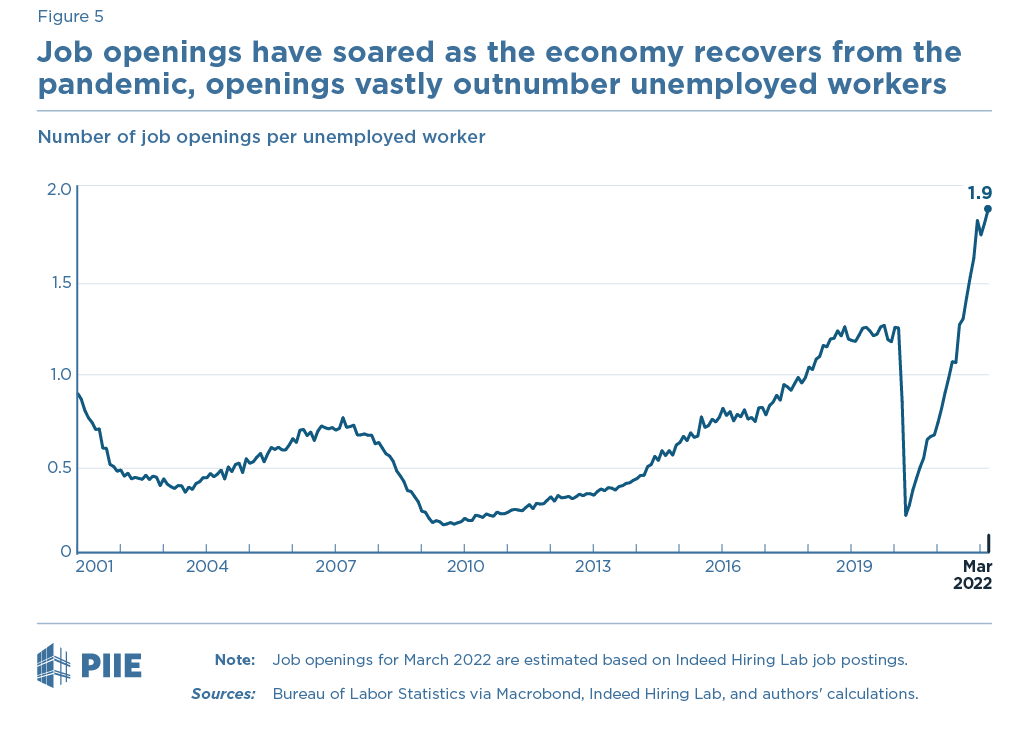

Labor markets remain tight, and wages are rising briskly

Labor demand continues to be very strong relative to labor supply. There are currently about 1.9 job openings for every unemployed worker—as shown in figure 5, about 50 percent higher even than during the robust labor market of the late 2010s. Against this backdrop, average hourly earnings rose 0.4 percent in March and are up 5.6 percent over the past year.

Figure 6 compares annualized growth in wages by industry sector over different time horizons. Industries are ordered by the 12-month growth rate, with the industry seeing the highest growth over the past year on the top and that seeing the lowest on the bottom. The chart shows variation in the evolution of wage growth by sector. For example, the leisure and hospitality sector has experienced very rapid wage growth on average over the past year, but the gains of recent months look more moderate. In contrast, wage growth in financial activities (which includes finance, insurance, and real estate) appears to have picked up in recent months.

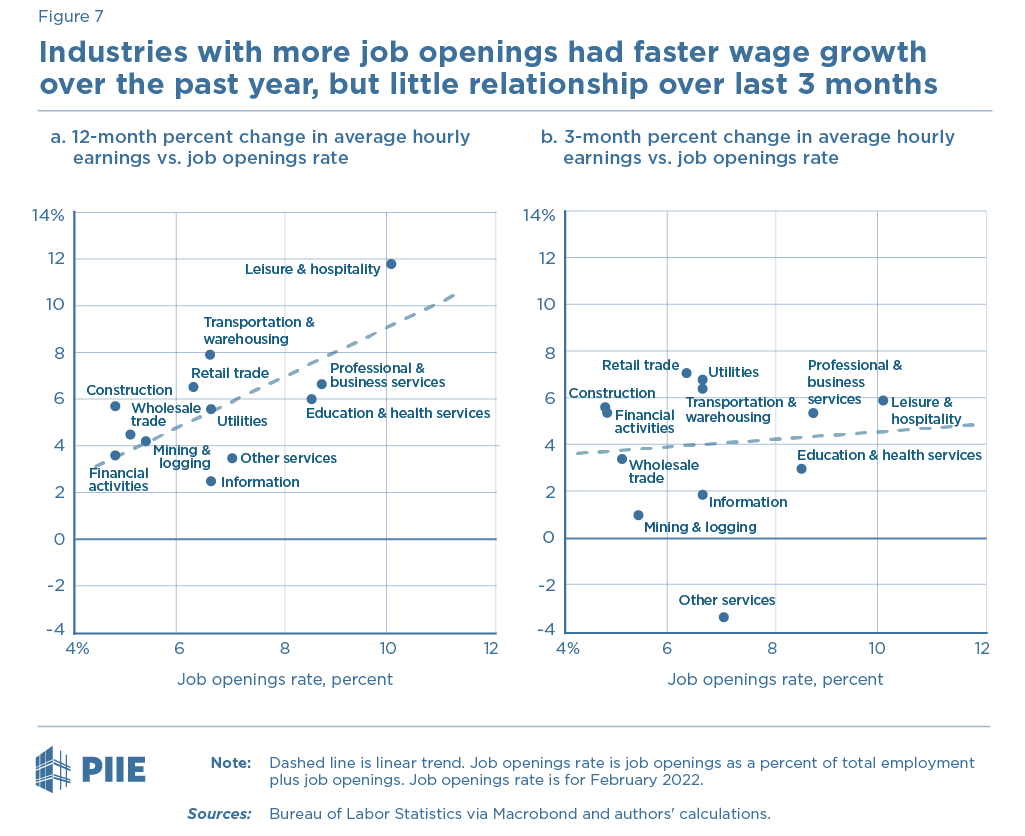

The strength of demand for workers in a sector is surely an important factor bearing on wage growth in that sector. Indeed, there is a pronounced positive correlation between the job opening rate and the 12-month growth rate of wages for different industries, as seen in the left panel of figure 7. However, there appears to be little link between job openings and earnings growth when looking over just the last three months. The weaker relationship may reflect more noise in these variables over the shorter time period, but it may also suggest that other factors are playing a larger role shaping wage growth now. The evolution of wage growth in coming months—and the consequent pressure on price inflation—will be an important consideration for the Federal Reserve as it decides how much to tighten monetary policy.

Data Disclosure

The data underlying this analysis are available here [zip].

Related Documents

- Fileemployment-2022-04-01.zip (472.86 KB)