Following the March 20 deal between the European Union (EU) and Turkey, the refugee flow from Turkey to Greece has declined from the levels in the earlier phases of the migration crisis in late 2015 and early 2016. The trend will likely lower the political pressure on many European leaders who negotiated the agreement, in which new migrants who arrive in Greece are to be sent back to Turkey on the condition that EU member states accept one Syrian refugee from Turkey for every one sent back.

Still, inflows into Greece remain nontrivial at more than 6,000 in the first two weeks of the agreement. If this level is sustained, more than 72,000 new refugees would come to Greece in roughly six months, implying that the EU and Turkey will have to negotiate a new arrangement before October.

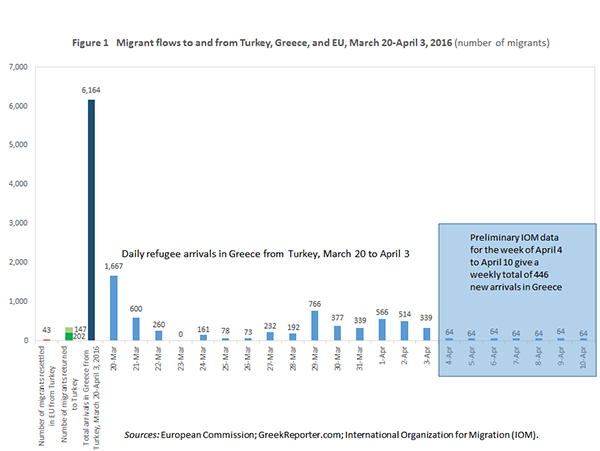

Figure 1 illustrates data on the main refugee flows between Turkey, Greece, and the EU since the deal became operational on March 20. The figure shows the disconnect between the number of refugees arriving in Greece from Turkey (6,164), the number of refugees returned to Turkey from Greece (202 + 147 after April 3), and the number of refugees resettled directly in the EU from Turkey (43).

In principle, under the deal, these three numbers should be roughly equal over time. If one is willing to classify Turkey as a "safe country," again in principle, all asylum applications from refugees coming from Turkey should be futile, as irregular migrants by definition face no threats or persecution there. Under the EU-Turkey deal's 1-1 principle, meanwhile, the EU is committed to resettle the same number of refugees returned from Greece directly in the EU from camps in Turkey.

The trend suggests, however, that in time the situation will stabilize. Refugee arrival data from more recent sources suggest that the daily inflow to Greece after April 3 has continued to drop. Preliminary data from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in figure 1 implies levels clearly politically manageable. Yet, the difficulties of returning new irregular migrants expeditiously to Turkey will continue. The legal right of each arriving new refugee for a personal evaluation of his/her asylum claim will remain virtually impossible for Greek and EU authorities to honor in less than several months. New irregular refugees are hence likely to continue to be stuck in Greece.

The failure of the EU-28—with a total population of more than 500 million—to initially resettle only 43 refugees from Turkey as part of this deal is an embarrassment. The 1-1 principle has become a 1-0.2 principle, covering only 0.7 percent of new irregular migrants arriving in Greece. Even allowing for President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's interest in securing visa-free travel for Turks to the Schengen Area of Europe, such discrepancies are unlikely to be sustained politically. The minute Erdogan senses that Turkey is actually not going to get the covered visa-free travel due to the lack of timely compliance with all 72 EU requirements, he would have a readily available excuse to tear up the deal.

On the other hand, the situation in the Aegean Sea is more politically acceptable in the rest of Europe, not least in Germany, where monthly asylum applications are down from 120,000 in December 2015 to 20,000 in March 2016—a level comparable to the average for all of 2014, when between 172,000 and 202,000 people applied for asylum.1 For Chancellor Angela Merkel and most other European leaders, the political emergency is largely over.

Did the EU-Turkey deal bring this situation about? Only partially. The bulk of the credit goes to the several border control measures implemented in recent months, notably the closing of the Macedonian-Greek border by the Macedonian government, which when it deems necessary continues to use armed force against would-be irregular migrants from Greece. Other Balkan countries maintain similar closed border policies, and Austria continues to implement a national maximum asylum quota policy.

The main Balkan route for migrants to Germany remains closed through various national border restriction policies. And while migrants are already seeking alternative routes through Bulgaria, Italy, and other countries, these inflows are unlikely to approach the levels of late 2015 through Greece northwards. Bulgaria and Albania would immediately replicate the Macedonian policy if flows through their territories increased, and the cost of the sea journey across the Mediterranean to Italy—where bigger boats are required—will be much higher than across the narrow Aegean Sea to Greek islands from Turkey. Numbers might reach the tens of thousands through such alternative routes but not levels high enough to become the kind of political emergency Europe experienced in late 2015 and early 2016. This is the conclusion, even allowing for the fact that only a tiny fraction of Syrian refugees in Turkey seem to have access to legal (e.g., at least the Turkish minimum wage) work there, and hence in time should be expected to have an economic interest in continuing onwards to Europe.

Another reason for the decline in refugee flows is that would-be migrants are very well informed about the situation on European borders (e.g., the squalid conditions in the Idomeni camp at the Greek-Macedonian border) and policies being implemented to keep them away and are thinking twice about turning over their life's savings to human smugglers to embark on a hazardous journey to Europe.

This change of heart is the reverse of what migrants had decided when they watched and listened to Angela Merkel declaring in 2015 that Germany's borders would be opened for unregistered migrants (e.g., not sent to Germany from official UN refugee camps). Many decided to take a chance then, but now they have seen barbed wire and rubber bullets on the Greek-Macedonian border and have increasingly decided not to go. Merkel should thank the people in Austria, Macedonia, and elsewhere, whom she criticized earlier for not implementing "national solutions," for solving her biggest domestic political problem.

The German government's two-faced stance on migration is further highlighted by its differing positions versus Austria and Italy. On the one hand, Chancellor Merkel has criticized Austria's national quotas on migration, but Germany is nonetheless considering lifting all border controls with Austria on May 12. Germany is also criticizing Italy—a country that has refrained from restricting migration across the Balkans—for not acting forcefully enough to prevent northward migrant flows.

The recent decline in refugee flows to politically manageable levels is a result of either deliberate policies or sheer luck but nonetheless is good news for short-term economic and political stability in Europe. Yet at the same time, it is clear that the recent reduction in inflows is at least partly reversible and has been achieved through the well-publicized imposition of physical hardships on arriving irregular migrants. And perhaps perversely but most discouragingly for proponents of deep reforms of Europe's entire legal migration framework like me, it is clear that a return to inward migration at 2014 levels removes the political crisis urgency required to generate the political will to make dramatic changes to the status quo. Instead the existing migration system will continue to stumble along with the usual resource constraints and inefficiencies.

As reflected in the 2016 Frontex Annual Risk Analysis, the most likely 2025 migration scenario is a "passive EU characterized by fragmentation, increasingly restrictive national border measures and few and inefficient common procedures." The EU will continue to be ill-equipped to deal with what is certain to be a sustained inward migration pressure in the future.

1. Eurostat data (migr_asyappctza) show a total of 202,645 asylum applications were submitted in Germany in 2014, of which 172,945 were first-time applications.