Like its Western neighbors, Eastern Europe is victim to a pervasive demographic challenge—the retirement of a growing number of elderly must be financed by a tax base of increasingly fewer younger workers.

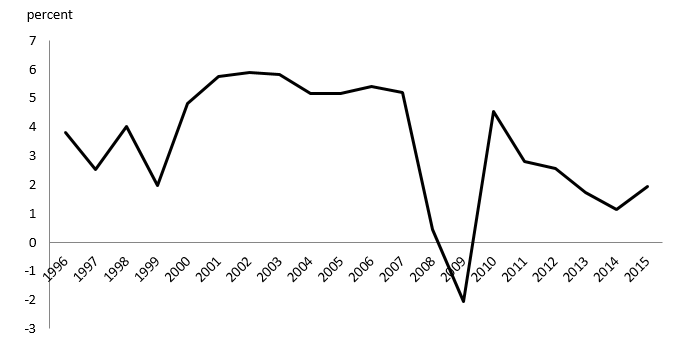

In order to compensate for these conditions, East European economies must redouble their efforts to boost productivity. All EU member states in Eastern Europe have used the European Union’s so-called convergence funds to invest heavily in infrastructure, on-the-job training, and upgrading industrial technology to facilitate productivity growth. And for a decade, starting in 1999, these investments paid off, with labor productivity rising above 5 percent per annum (figure). The euro area crisis reversed this trend, and productivity growth has not recovered to precrisis levels.

Labor productivity in Eastern Europe, 1996–2015

Note: Countries include: Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia.

Source: Eurostat 2016.

A major reason lies with East European firms. Recent research identifies management practices in the areas of operations, monitoring, targets, and incentives as hampering productivity for all but large, export-oriented firms. Compared with Israel and some Western European countries, Eastern Europe has a higher percentage of firms with low productivity in their respective sectors.

Another venue for increasing productivity is providing nonbank financing options. Access to finance for the average East European company has been largely limited to bank credit. That source of financing rapidly dried up during the euro area crisis and has not recovered, as banks in the region have continued to deleverage. An alternative source of financing, through private equity or capital markets, is slow to develop. Private equity investment accounts for more than 1 percent of GDP in developed economies but for less than 0.1 percent in Eastern Europe, including in high-growth markets like Poland. Yet its benefits for the growth and competitiveness of firms are well documented. Increases in operating revenue are 35 percent stronger for firms that receive private equity investment relative to their peers in the region, and productivity growth is 17 percent higher. Up to 40,000 firms in Eastern Europe could potentially attract private equity funding, more than 50 times the number of companies that have actually received such financing in recent years.

Eastern Europe also has to play catch-up with Western Europe, America, and parts of Asia in many high-tech fields. According to Forbes, only 11 of the world's 100 most innovative tech companies in 2015 were based in Europe and none in the new member states. Reuters assesses that only 17 of the top 100 global innovators in any industry are European companies, 11 of which are headquartered in the United Kingdom and 6 in Western Europe. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s rankings suggest only 6 of the world’s 50 smartest companies in 2016 are European, none based in Eastern Europe.

Eastern Europe also has to play catch-up with Western Europe, America, and parts of Asia in many high-tech fields.

One reason East European companies fail to rank on these lists is related to their small market size and disparate national regulations. A new social media site in Hungary has only 10 million potential users unless it translates its content into other languages. Because of differences in culture across European countries, it would need a new interface, a different marketing strategy, and probably other advertisers to appeal to a larger European customer base. That would mean dealing with new regulations and multiple tax schemes.

A second reason is the shortage of venture finance in the region. Silicon Valley and Route 128 near Boston combine a deep talent pool of researchers with easy access to start-up and venture financing. This combination attracts not only entrepreneurs in new tech businesses but also companies that provide them with management consulting or infrastructure support. Asian high-tech hubs, such as Singapore, Taiwan, and Bangalore, also have financial and human capital. Israel offers similar advantages in its high-tech incubators near Haifa and Tel Aviv.

In contrast, Europe’s financial services are not directed toward start-ups. European venture capital fundraising was $5 billion in 2015, only about one-tenth of that in the United States. Start-ups may find early-stage financial backing of up to $500,000, and later-stage support of more than $10 million, thanks to various EU-wide schemes, for example by the European Investment Bank. But Eastern Europe’s tech companies regularly struggle to land the investment needed to bridge the early and mature stages of development.

These weaknesses need to be addressed promptly so that productivity can reach precrisis levels, and economic convergence with the rest of Europe, now on hold, can restart.