If you have a serious interest in sanctions and sanctions evasion, you should be taking a close look at the ZTE case. The $900 million settlement against the Chinese telecomm firm—the largest civil penalty ever levied in a Commerce export control case—was completely warranted. Even Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s response was muted (“The Chinese government consistently opposes foreign governments putting unilateral sanctions on Chinese companies. At the same time, we have always asked our companies to operate legally abroad"). But two things stand out from a review of the case. First, firms that want to get around sanctions will go to extraordinary lengths to get around them. Second, these cases are difficult to prosecute, and require an alignment of investigative journalism, errors on the part of the perpetrators, and ample resources dedicated to the case.

The significance of the case was underlined by the fact that Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross personally announced the settlement. Clearly, all of the heavy lifting had been done under the Obama administration, but acting on it is a good sign. I can do no better than simply paraphrasing Commerce’s discussion of how the case unfolded.

The investigation spanned a number of agencies: attorneys general, Homeland Security, FBI, Justice and Commerce (Bureau of Industry and Security). Interestingly, Commerce admits that the investigation followed allegations of illegal conduct in the media by Reuters, underlining the importance of good journalism and open-source work. The case initially focused on shipments to Iran and resulted in an administrative subpoena of ZTE’s U.S. affiliate, ZTE USA. In 2016, the Department of Commerce sanctioned ZTE by adding it to the Entity List, requiring licenses to export, reexport, or transfer items subject to export controls. The company was shipping hardware and software from top U.S. technology companies to Iran's largest telecoms carrier and was subsequently found to have similar projects to circumvent export controls to North Korea, Syria, Sudan and Cuba as well.

The decision for tighter licensing seems lax, but could have been associated with gathering evidence for a firmer case. The pace appears to have accelerated when two internal documents came to light that are in effect sanctions-busting manuals. ZTE was also found to have engaged in a scheme to prevent disclosure by scrubbing documents from the outside counsel and forensic accounting firm that ZTE had retained during the investigation, not exactly the way to win sympathy with the investigation.

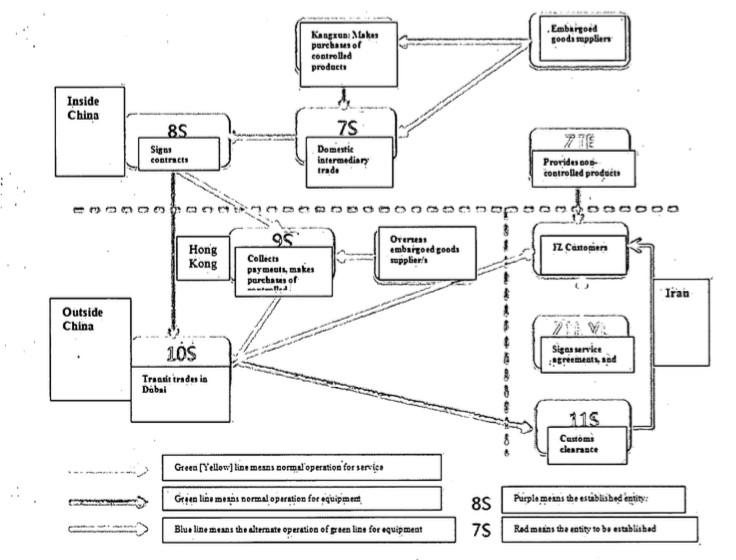

What is both well-known among sanctions watchers—but nonetheless amazing to see in print—is the content of the two manuals, which are posted on the Commerce website. Conspiracies do not simply happen by inadvertence; they are planned, and meticulously too. The euphemistic title of one document is “Proposal for Import and Export Control Risk Avoidance” and is marked “Top Secret Highly Confidential.” The reasons for the security quickly become obvious. The document outlines two approaches—a fully-detached and partly-detached shell company option—that involve chains of newly-created entities in Hong Kong and the Gulf, with instructions down to how they will be set-up and registered, boards and ownership, staffing, financing, the movement of goods, and even packaging and the management of customs issues. The schematic from the report below gives some sense of the complexity and nuance of these operations. And for the record, these are not shipments of textiles or ramen. 283 shipments to North Korea apparently included routers, microprocessors and servers, in short items that could easily end up in military-related purposes.

A colleague pointed out to me that there is a silver lining to the case: that in the end, ZTE did fully acknowledge culpability, fired three senior executives and moved toward greater transparency of operations. This cooperation accounts for why a portion of the fine was held in abeyance as a kind of probation. If Chinese officials as well as ZTE management were involved in moving toward this deal, it would be a good sign for the future of sanctions enforcement. But whatever Xi Jinping and Donald Trump manage to agree on regarding North Korea at the Mar-a-Lago summit, there is no reason for the US to cease and desist with respect to this particular type of sanction. This is not tactical—a way of getting North Korea back to the bargaining table—but fundamentally defensive: an effort to protect the US and its allies against North Korean capabilities.